My site recently had some struggles, and so I needed to completely rebuild it. Below are some archive posts from the old site:

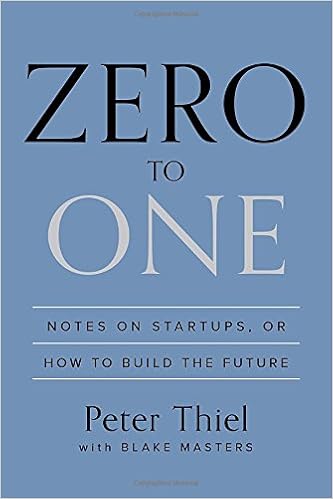

A man I greatly admire recently recommended I read the book Zero to One, by Peter Thiel. I’m really glad I followed this advice because I found that this book seriously succeeded in my main criteria for judging literature – it challenged and changed the way I thought. The main premise of the book is that many of us (me!) focus on making marginal improvements to existing products. But what we need are more breakthrough products – things that don’t even exist (hence going from zero to one). Yes I could write a book or make a movie, but there are millions of those. Is there something new? Thiel writes:

“Every moment in business happens only once. The next Bill Gates will not build an operating system. The next Larry Page or Sergey Brin won’t make a search engine. And the next Mark Zuckerberg won’t create a social network. If you are copying these guys, you aren’t learning from them” (1).

And also, “When we think about the future, we hope for a future of progress. That progress can take one of two forms. Horizontal or extensive progress means copying things that work—going from 1 to n. Horizontal progress is easy to imagine because we already know what it looks like. Vertical or intensive progress means doing new things—going from 0 to 1. Vertical progress is harder to imagine because it requires doing something nobody else has ever done. If you take one typewriter and build 100, you have made horizontal progress. If you have a typewriter and build a word processor, you have made vertical progress” (7).

Thiel states that there are seven questions to answer before you can go from zero to one:

- “The Engineering Question: Can you create breakthrough technology instead of incremental improvements?

- The Timing Question: Is now the right time to start your particular business?

- The Monopoly Question: Are you starting with a big share of a small market?

- The People Question: Do you have the right team?

- The Distribution Question: Do you have a way to not just create but deliver your product?

- The Durability Question: Will your market position be defensible 10 and 20 years into the future?

- The Secret Question: Have you identified a unique opportunity that others don’t see?” (153-154).

To me, the most insightful questions from the above were the first and the last. How big must the breakthrough be? Thiel argues, “As a good rule of thumb, proprietary technology must be at least 10 times better than its closest substitute in some important dimension to lead to a real monopolistic advantage. Anything less than an order of magnitude better will probably be perceived as a marginal improvement and will be hard to sell, especially in a crowded market” (48).

I also appreciated Thiel’s insight that having an awesome product isn’t enough. He said not to underestimate the importance of sales, marketing, public relations, and other modes of shaping public opinion. “Even the agenda of fundamental physics and the future of cancer research are the results of persuasion. The most fundamental reason that even businesspeople underestimate the importance of sales is the systematic effort to hide it at every level of every field in a world secretly driven by it” (129).

The last question though – about secrets – was by far my favorite. I love using Uber. How come I didn’t think of it 5 years ago? I love using Facebook. But 15 years ago, I didn’t even think about connecting online with people I had met previously. What other things would I really love, but I’m not even currently aware they exist? These are the secrets. From Thiel:

“The actual truth is that there are many more secrets left to find, but they will yield only to relentless searchers. There is more to do in science, medicine, engineering, and in technology of all kinds. We are within reach not just of marginal goals set at the competitive edge of today’s conventional disciplines, but of ambitions so great that even the boldest minds of the Scientific Revolution hesitated to announce them directly. We could cure cancer, dementia, and all the diseases of age and metabolic decay. We can find new ways to generate energy that free the world from conflict over fossil fuels. We can invent faster ways to travel from place to place over the surface of the planet; we can even learn how to escape it entirely and settle new frontiers. But we will never learn any of these secrets unless we demand to know them and force ourselves to look.

“The same is true of business. Great companies can be built on open but unsuspected secrets about how the world works. Consider the Silicon Valley startups that have harnessed the spare capacity that is all around us but often ignored. Before Airbnb, travelers had little choice but to pay high prices for a hotel room, and property owners couldn’t easily and reliably rent out their unoccupied space. Airbnb saw untapped supply and unaddressed demand where others saw nothing at all. The same is true of private car services Lyft and Uber. Few people imagined that it was possible to build a billion‐ dollar business by simply connecting people who want to go places with people willing to drive them there. We already had state‐licensed taxicabs and private limousines; only by believing in and looking for secrets could you see beyond the convention to an opportunity hidden in plain sight. The same reason that so many internet companies, including Facebook, are often underestimated—their very simplicity—is itself an argument for secrets. If insights that look so elementary in retrospect can support important and valuable businesses, there must remain many great companies still to start” (102-103).

“The best place to look for secrets is where no one else is looking. Most people think only in terms of what they’ve been taught; schooling itself aims to impart conventional wisdom” (104-105).

Another potential for finding secrets is to consider this statement: “The most valuable companies in the future…[will] ask how can computers help humans solve hard problems” (150).

This book is forcing me to more carefully examine how I am allocating my priorities. I’m pretty good at copying and doing things efficiently. But I am spending time spinning my wheels when I could be building someting from zero to one? I am intrigued at this personal insight from Thiel’s life: “The highest prize in a law student’s world is unambiguous: out of tens of thousands of graduates each year, only a few dozen get a Supreme Court clerkship. After clerking on a federal appeals court for a year, I was invited to interview for clerkships with Justices Kennedy and Scalia. My meetings with the Justices went well. I was so close to winning this last competition. If only I got the clerkship, I thought, I would be set for life. But I didn’t. At the time, I was devastated.

“In 2004, after I had built and sold PayPal, I ran into an old friend from law school who had helped me prepare my failed clerkship applications. We hadn’t spoken in nearly a decade. His first question wasn’t ‘How are you doing?’ or ‘Can you believe it’s been so long?’ Instead, he grinned and asked: ‘So, Peter, aren’t you glad you didn’t get that clerkship?’ With the benefit of hindsight, we both knew that winning that ultimate competition would have changed my life for the worse.… It’s hard to say how much would be different, but the opportunity costs were enormous. All Rhodes Scholars had a great future in their past” (36-37).

Important words to consider!

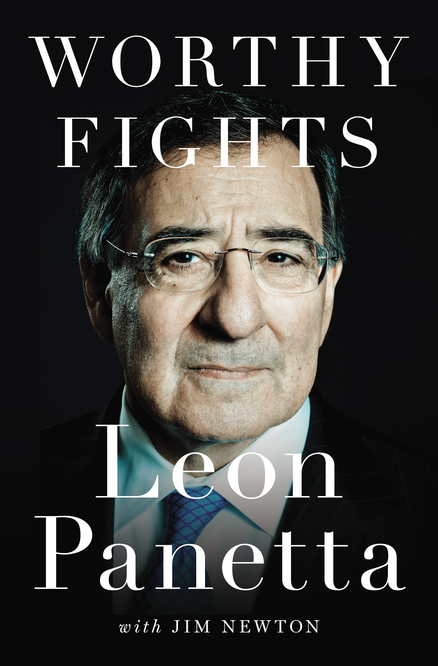

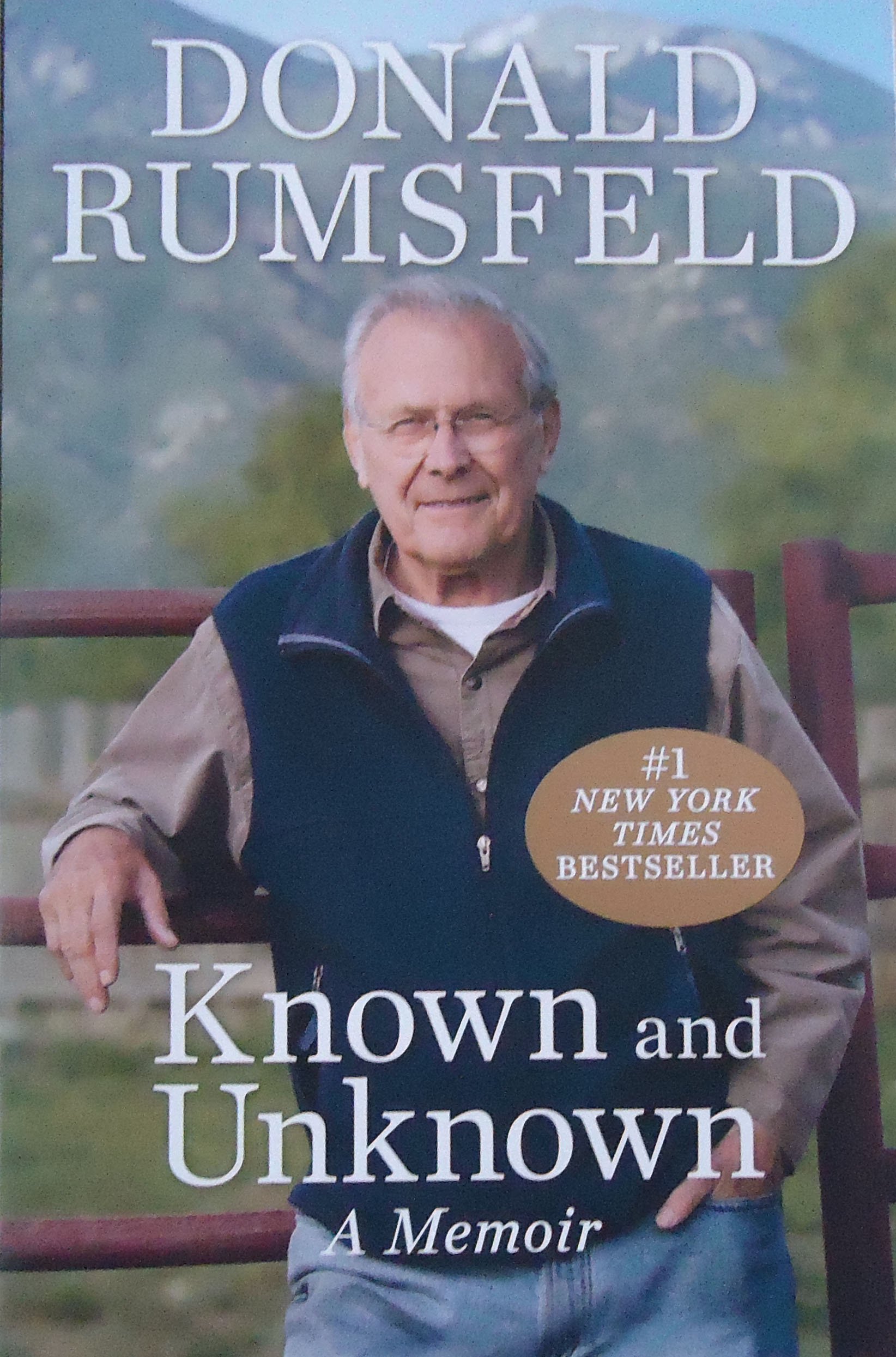

I recently read a trio of books from two former Secretaries of Defense: Worthy Fights, Known and Unknown, and Rumsfeld’s Rules. While these two politicians came from different parties and have different points of view, I learned a lot from both of them. One of my biggest overall takeaways is the importance of the “little people” in an administration. The POTUS tends to get all of the credit (or blame) for the things that happen, but these books illustrated that there are many decision makers working hard on any given policy or decision and the leader needs to be surrounded with very good people.

A few thoughts from these books:

- Both hammered home the importance of leaders having a personal touch with people. Little things that have a personal touch, like “calling up the mother of a city council member and wishing her a happy birthday” (Panetta, p. 48) or George W. Bush talking with the Rumsfelds about their family’s personal struggles go a long way.

- I was very impressed wtih how both Panetta and Rumsfeld dealt with significant failures that hit them early in their careers. They did not quit, they didn’t whimper, they picked themselves up and kept on moving. Panetta noted a few lessons: “I’d been naive not to cultivate a better relationship with the White House…and I’d made the rookie mistake of assuming that because I believed so strongly in our mission others would come around” (p. 44).

- Panetta’s recounting of the battle for the 1993 budget was extremely inspiring. It came down to one vote and Panetta (and others) went to great lengths to pass this bill. To me, efforts to lower the budget deficit are a no-brainer. But Panetta didn’t trust in the idea that people would come around to common sense, rather he worked overtime to make sure that the vote would go his way. “And it all came down to one vote in the House and one in the Senate. Leadership matters” (p. 122).

- I was impressed with Rumsfeld’s statement to the effect that if you are accomplishing important things, you are bound to be criticized. Yes we need to be mindful of criticism and look for ways that we can improve, and at the same time, you are not going to please everyone, and if nobody is being critical, maybe you aren’t pushing hard enough.

- Finally, there is the quote that Rumsfeld is famous for (although the ideas did not originate with him). “Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.” This has obvious implications for many areas of life.

Whether you agree or disagree with the politics of these individuals, I think you’ll enjoy all of these books.

From roughly the beginning of time untilof the fall 2015, only a handful of articles have been published that focus on the efficacy of OER. A few more have been published that rigorously examine the perceptions of students and teachers who have used OER and compared them to traditional materials. I have been focusing on collating these research studies so that we can synthesize across multiple studies and see a bigger picture. I’m pleased to announce that I recently published an in-depth article focusing on empirical research relating to perceptions and efficacy in the journal Educational Technology Researcy and Development. Please access the open-access version of this article. If you just want the short version, see these slides (which actually include more articles than the article itself):

Warning – this is a very long post! I recently read the book,How Not to Be Wrong by Jordan Ellenberg, and loved it. While I have some small quibbles, the book pointed out fallacies in my thinking and strengthened my ability to think more effectively. Ellenberg did this in part by posing interesting puzzles, almost all of which I got wrong, which of course made me want to dig deeper.

The first example of such a puzzle comes when Ellenberg tells the story of Abraham Wald, a mathematician who gave advice to the US military during World War II. At issue was where to put additional armor on the planes. Too little armor didn’t provide adequate protection, and of course too much would make the planes too heavy and harder to maneuver. So with that background, try this puzzle:

The military had analyzed bullet holes in aircraft that had returned from combat and found the following:

| Section of the Plan |

Bullet holes per square foot |

| Engine |

1.11 |

| Fuselage |

1.73 |

| Fuel System |

1.55 |

| Rest of the plane |

1.8 |

The question they asked was “Where should we put more armor?” Wald responded essentially by saying “You are asking the wrong question?” Why is this the wrong question?

Wald explained they were asking the wrong question because they were only examining the planes that came back. The real question is, “What happened to the planes that didn’t come back?” Further analysis showed that when a plane was hit in the engine it likely went down and so wasn’t included in the sample. The lesson is now obvious – don’t just examine the evidence that you have; instead, think also about the evidence that you don’t have.

A real-life example of this phenomenon could be considering student reviews for a class. Suppose that a class gets really solid reviews, but the class was only half full. I might ask, “Was the class full on the first day of class? If so, what happened to the other half of the class? Why did they choose to drop after 1-2 class periods?” That line of questioning could lead to a different conclusion than just looking at the reviews of those who stayed.

***

One issue that Ellenberg deals with early on in the book is the tendency we have to utilize linear thinking. He examines a CATO blog post entitled, “Why Is Obama Trying to Make America More Like Sweden when Swedes Are Trying to Be Less Like Sweden?” Simplifying the subject (more on that in a moment) Ellenberg suggests the author of the blog post must have a chart like this in his head:

Ellenberg says, “Acording to the chart, the more Swedish you are [meaning in a footnote, the ‘quantity of social services and taxation’], the worse off your country is. The Swedes, no fools, have figured this out and are launching their northwestward climb toward free-market prosperity.”

Ellenberg continues though, by drawing a different picture:

Ellenberg states, “This picture gives very different advice about how Swedish we should be. Where do we find peak prosperity? At a point more Swedish than America, but less Swedish than Sweden. If this picture is right, it makes perfect sense for Obama to beef up our welfare state while the Swedes trim theirs down” (p. 22)

I admit that in a lot of areas, my first instinct is to think in a linear fashion, when non-linear thinking is required. This was a great example, but I do want to raise a quibble that is representative of the whole book. Throughout, Ellenberg consistently picks on conseratives and makes them (as well as believers in God) the brunt of many of his points. I think this is unfair as mathematical mistakes are in abundance and it would been nicer to spread the glory (or blame) around. In this particular instance, Ellenberg really ripped into the author of the Cato blog post. In doing some fact-checking, I learned that the author of the Cato study has specifically pointed to a non-linear approach for this type of question.

The short story is that the Cato author utilizes “the Rahn Curve” and argues that both the US and Sweden are to the right of the peak performance point.

My main issue here isn’t with which graph is correct, or where Sweden and the US are – either way, it points out the dangers of linear thinking and promotes further discussion. My disappointment is that Ellenberg basically creates a caricature out of the Cato blogger and misrepresents his work. That doesn’t seem fair to me, and it made me wonder how many times throughout the book there were other instances like that.

***

Ellenberg next takes on another difficult area – the misuse of regression by telling an interesting story. In 2008, about 66 per cent of the US population was overweight, and trends showed that the rate of obesity is increasing. These statistics led researchers to ask the question when will all Americans be overweight? They used a scatterplot of past years and obesity rates and determined that if past trends continued by 2048 all Americans will be obese. ABC News picked up on this story calling it an “obesity apocalypse.” All of this was based on data that looks something like this:

It’s back to the false idea of linearity. Due to genetics and other factors, there will likely always be skinny people, even if obesity trends overall increase. But this line will likely flatten out – if it was really a linear line Ellenberg points out that “a whopping 109% of Americans would be overweight” by 2060 (p. 60).

If we do not carefully think about the mathematical underpinnings of this study we could easily jump to the wrong conclusions. Because “the higher the proportion of overweight people, the fewer skinny malinkies are left to convert, and the more slowly the proportion increases towards 100%” (p. 60).

The lesson? Drawing regression lines from a scatterplot is “versatile, scalable, and as easy to execute as clicking a button on your spreadsheet. That’s a weakness as well as a strength. You can do linear regression without thinking about whether the phenomenon you’re modeling is actually close to linear. But you shouldn’t.” (p. 53).

***

In chapter 4 Ellenberg discusses the law of large numbers. He points out that South Dakota has the highest brain cancer rate in the US, while North Dakota has one of the lowest brain cancer rates. What is the difference between North and South Dakota that is causing such a gap? While my mind is racing towards a possible solution (mining? water quality?), he points out that of the nine states that finished at the top and bottom of the brain cancer rate lists, all of them were among the smallest 14 states (by population) in the US. In other words, in small populations there is going to be a lot more variation because the population isn’t sufficiently large to account for random fluctuations.

Ellenberg connects this with the common practice of using proportions to help people understand the scope of a situation. For example, if 1,074 Israelis are killed by terrorists (that is ~ .015% of the Israeli population) would that be equivalent to 50,000 Americans being killed (.015% of the US population) or one or two people from Tuvalu (population 9,847) being killed?

There are some problems with applying proportional logic to deaths: “If you rate your bloodshed by proportion of national population eliminated, the worst offenses will tend to be concentrated in the smallest countries. Matthew White, author of the agreeably morbid Great Big Book of Horrible Things, ranked the bloodlettings of the twentieth century in this [proportional] order, and found that the top three were the massacre of the Herero of Namibia by their German colonists, the slaughter of Cambodians by Pol Pot, and King Leopold’s war in the Congo. Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and the big populations they decimated don’t make the list” (p. 75).

Ultimately, the idea Ellenberg puts forward in this chapter is while proportions matter, one has to be very careful in how they are utilized.

***

Ellenberg continues this idea when he states an important rule: “Don’t talk about percentages of numbers when the numbers might be negative” (p. 78). He poses a complicated problem:

In June of 2011 the US added only 18,000 jobs. That same month, the state of Wisconsin added 9,500 jobs and reported, “Over 50 percent of U.S. job growth in June came from our state.” Is that true? Ellenberg points out that neighboring Minnesota added more than 13,000 jobs that same month. So it could claim responsibility for 70% of the nation’s job growth. But how could Wisconsin and Minnesota account for 120% of the nation’s job growth?

The answer of course is in negative numbers. Some states (like Minnesota and Wisconsin) gained jobs in June of 2011, but many states lost jobs. Essentially the “job losses in other states almost exactly balanced out the jobs created” and so both Wisconsin and Minnesota “could both in this technically correct but fundamentally misleading way, be right” (p. 80).

***

Another interesting puzzle: A stockbroker from Baltimore sends you an unsolicited newsletter each week predicting a stock that is about to go up. To your astonishment he is correct ten weeks in a row. You compute the odds of this as being less than .1% and are therefore willing to shell out several hundred dollars when on the eleventh week his letter requests payment before continuing to send future newsletters. But is there a catch?

It turns out there is. This Baltimore stockbroker actually send out two newsletters each week. Week #1, 10,000 newsletters went out, half of which said a stock would go up with the other half stating it would go down. The following week, he does the same thing with a different stock, but he only mails the newsletter to 5,000 people (the ones who received the version of the newsletter with the correct guess). After ten weeks there isn’t a big pool of people left, but those people all believe the stockbroker is a genius.

While this is perhaps an improbable scenario (think of the costs of mailing all those letters) it’s actually easy to see how this exact same scam could be done verily easily (and inexpensively) with electronic advertising.

Ellenburg connects this with a much more serious issue, that of scientific journals publishing only studies that show statistical significance. Just like the stockbroker from Baltimore doesn’t tell you about his false findings, academics don’t tell you about the findings that are not significant. This is particularly important if the number of unpublished studies is large. For example, the test of statistical significance is often set at 5%. In other words, if your study statistically measures that the odds of results happening by chance are less than 5% you have a “significant” study. Imagine twenty scientists each run a study to determine a link between eating sugar and hair loss (I made this up). Nineteen find no connection, and therefore do not publish their results. One person does find significant results (and since this is 1/20 = 5% we would expect this by random chance). This person does publish the study and we all stop eating sugar. Ellenburg uses the following xkcd comic strip to illustrate this exact point:

The point – unlikely things do happen! To make major decisions on something that has only a 5% probability of being wrong seems like a sure bet – except there’s still a 5% chance it’s wrong. One solution is to look for studies that have been successfully replicated multiple times – something that is all too rare. As Ellenberg writes, “It’s tempting to think if ‘very improbable’ as meaning ‘essentially impossible,’ and from there, to utter the word ‘essentially’ more and more quietly in our mind’s voice until we stop paying attention to it. But impossible and improbably are not the same – not even close. Impossible things never happen. But improbable things happen a lot” (p. 136-137).

Bottom line – Be careful! It’s possible that “Most Published Research Findings Are False” (although some now claim that those findings are false!)

***

One of my favorite anecdotes from the book is the following: On October 18, 1995, the UK Committee On Safety of Medicines (CSM) sent a letter to physicians throughout the country warning that certain brands of oral contraceptives would double the risk of venous thrombosis (venous thrombosis leads to death). The AP Headline that ran on October 19, 1995 said, “GOVERNMENT WARNS SOME BIRTH CONTROL PILLS MAY CAUSE BLOOD CLOTS.” One physician reported that 12 per cent of users stopped on the day of the announcement.

The result? Conceptions in England and Wales (which had fallen for three years in a row) rose by 26,000 in 1996. There were also 13,600 more abortions in 1996 than 1995.

Ellenberg writes, “That might seem a small price to pay to avoid a blood clot careening through your circulatory system…think about all the women who were spared from death…! But how many women, exactly is that?” (p. 119). It turns out that while the pills doubled a women’s risk of thrombosis, this risk is only 1 in 7,000. So “doubling” the risk leads to a rate of 2 in 7,000. In other words by avoiding “doubling the risk” of thrombosis researchers may have inadvertently increased risks due to birth complications and other factors.

Another interesting example he raises is that one study found that infants cared for by home-based day care were seven times more likely to die than kids at day care centers. Sounds serious. But considering that the fact that both sets of numbers are extremely low compared to other factors. For example, according to the study there were twelve babies who died in home based daycare. Compare that to the 79 infants who died in car accidents – “If your baby ends up spending 20% more time on the road per year thanks to [traveling to a daycare center], you may have wiped out whatever safety advantage you gained by choosing the fancier day care” (p. 120).

The bottom line: “Risk ratios applied to small probabilities can easily mislead you” (p. 120).

***

Another puzzle: Suppose that Facebook develops “a method for guessing which of its users are likely to be involved in terrorism against the United States…are there words that appear more frequently in their updates? Bands or teams or products they’re unusually prone or disinclined to like?” (p. 166). Putting all this information together, let’s suppose that Facebook gathers a list of 100,000 people and says, “People drawn from this group are about twice as likely as the typical Facebook user to be terrorists or terrorism supporters.” Ellenberg asks, “What would you do if you found out a guy on your block was on that list? Would you call the FBI?” (p. 167).

Twice the risk! Sounds scary. But let’s step back from the numbers. Let’s assume that there are 200 million Facebook users in America and 10,000 of them are terrorists. So that means that 1 in 200,000 Facebook users are terrorists. Let’s “take Facebook at their word, that their algorithm is so good that the people who bear its mark are fully twice as likely as the average user to be terrorists. So among this group, one in ten thousand, or ten people will turn out to be terrorists, while 99,990 will not. If ten out of the 10,000 future terrorists are in the upper left [of the below box], that leaves 9,990 for the upper right. By the same reasoning: there are 199,990,000 nonoffenders in Facebook’s user base, 99,990 of whom were flagged by the algorithm and sit in the lower left box; that leaves 199,890,010 people in the lower right….Somewhere in the four-part box is your neighbor down the block. But where?” (p.168)

“in a way, this is the birth control scare revisited. Being on the Facebook list doubles a person’s chance of being a terrorist, which sounds terrible. But that chance starts out very small, so when you double it, it’s still small.

But there’s another way to look at it, which highlights even more clearly just how confusing and treacherous reasoning about uncertainty can be. Ask yourself this – if a person is in fact not a future terrorist, what’s the chance that they’ll show up, unjustly, on Facebook’s list? In the box, that means if you’re in the bottom row, what’s the chance that you’re on the left-hand side?” (p. 168).

Turns out that 99,990/199,990,000 is .05%. So “An innocent person has only a 1 in 2,000 chance of being wrongly identified as a terrorist by Facebook….In other words, under the rules that govern the majority of contemporary science, you’d be justified in rejecting the null hypothesis and declaring your neighbor a terrorist. Except there’s a 99.99% chance he’s not a terrorist. On the one hand, there’s hardly any chance that an innocent person will be flagged by the algorithm. At the same time, the people the algorithm points to are almost all innocent. It seems like a paradox, but it’s not. It’s just how things are…Here’s the crux. There are really two questions you can ask. They sound kind of the same, but they’re not.

“Question 1: What’s the chance that a person gets put on Facebook’s list, given that they’re not a terrorist?

“Question 2: What’s the chance that a person’s not a terrorist, given that they’re on Facebook’s list?

“We’ve already seen that the answer to the first question is about 1 in 2,000 while the answer to the second is 99.99%. And it’s the answer to the second question that you really want” (p.169).

Having a Bayesian outlook can help us filter out this type of question by working hard to carefully contemplate a priori probabilities.

***

Ellenberg has a fabulous section on regression to the mean. I read about this in Thinking Fast and Slow but this was a good reminder. Borrowing from Sam McNerney’s summary of How Not to be Wrong:

“Suppose you’re an average golfer but you’ve been playing terribly. You take a lesson with the pro, and, lo and behold, you play better the next round. Credit to the pro, right? Maybe. But your golf game revolves around an average—a mean—and chances are that in the short term, you’ll regress toward that average after a string of awful or superb rounds.

“Is performance in business also subject to regression toward the mean effects?

“Ellenberg mentions a study conducted by Northwestern University professor of statistics Horace Secrist. Secrist tracked 49 department stores between 1920 and 1930 and discovered that the stores with the highest average profits performed steadily worse throughout the decade and vice versa. He concluded that businesses were “converging on mediocrity,” but there is no “mysterious mediocrity-loving force,” just the fact that in business, as in sports, performance depends on skill and luck. The firms with the fattest profits in 1920 were well managed, but they were also lucky. Ten years later, management remained superior, but luck ran out.

“Regression toward the mean is a bit unsettling if you think about it. No matter how hard you work at your golf game, and no matter how many smart people you employ, performance will always partially depend on events out of your control. “In fact,” Ellenberg writes, “almost any condition in life that involves random fluctuations in time is potentially subject to the regression effect [p.302.]””

“Did you try a new…diet and find you lost three pounds? Think back to the moment you decided to slim down. More than likely it was a moment at which the normal up-and-down of your weight had you at the top of your usual range…but if that’s the case you might well have lost the three pounds anyway…[diet or no diet] when you trended back toward your normal weight” (p. 302-303).

Ellenberg provides several other interesting examples of regression to the mean, I’ll just share one more. He quotes from a 1976 medical journal paper on bran. The researchers “recorded the length of time a meal spent in the body between entrance and exit before and after the bran treatment. They found that bran has a remarkable regularizing effect. ‘All those with rapid times slowed down towards 48 hours…those with medium length transits showed no change…and those with slow transit times tended to speed up towards 48 hours. Thus bran tended to modify both slow and fast initial transit times towards a 48-hour mean.’ This of course, is precisely what you’d expect [regression towards the mean] if bran had no effect at all” (p. 309).

***

Ellenberg points out that we typically think of correlation as identifying linear relationships between variables. But, “just as not all curves are lines, not all relationships are linear” (p.345). The below picture represents voters – the horizontal axis is left (liberal) to right (conservative) and the vertical access measures knowledge. What the “heart-shaped” correlation shows is that the more informed a vote is the more polarized they become. While Ellenberg notes that this is more of an illustration and shouldn’t be taken for social science research, he states, “The graph reflects a sobering social fact, which is by now commonplace in the political science literature. Undecided voters, by and large, aren’t undecided because they’re carefully weighing the merits of each candidate, unprejudiced by political dogma. They’re undecided because they’re barely paying attention” (p. 346).

***

Another key point that Ellenberg raises is the difficulty around “public opinion.” Here’s a puzzle. “In a January 2011 CBWS News poll, 77% of respondents said cutting spending was the best way to handle the federal budget deficit, against only 9% who preferred raising taxes…A Pew Research poll from February 2011 asked Americans about thirteen categories of government spending: in eleven of those categories, more people wanted to increase spending rather than dial it down” (p. 366). The only two sections people were willing to cut (foreign aid and unemployement insurance) accounted for less than 5% of 2010 spending. In other words, the public wants to cut spending, except it doesn’t. How can this be?”

Ellenberg tackles this issue with a word problem: “Suppose a third of the electorate thinks we should address the deficit by raising taxes without cutting spending; another third thinks we should cut defense spending; and the rest think we should drastically cut Medicare benefits. Two out of three people want to cut spending; so in a poll that asks “Should we cut spending or raise taxes” the cutters are going to win by a massive 67-33 margin. So what to cut? If you ask, “Should we cut the defense budget?” you’ll get a resounding no: two-thirds of voters – the tax raisers joined by the Medicare cutters-want defense to keep its budget” (p. 367). The upshot? “Each voter has a perfectly rational, coherent political stance. But in the aggregate, their position is nonsensical” (p. 367).

Another example that shows how one needs to dig deeper than the headlines: “In an October 2010 poll of likely voters, 52% of respondents said they opposed [the Affordable Care Act], while only 41% supported it. Bad news for Obama? Not once you break down the numbers. Outright repeal of health care reform was favored by 37%, with another 10% saying the law should be weakened; but 15% preferred to leave it as is, and 36% said the ACA should be expanded…that suggests that many of the law’s opponents are to Obama’s left, not his right. There are (at least) three choices here: leave the health care law alone, kill it, or make it stronger. And each of the three choices is opposed by most Americans” (p. 368). Thus depending on where you go for news, you might see a headline line “The Majority of Americans Oppose Obamacare” or “Majority of Americans want to keep of strengthen Obamacare!” (p. 368).

It’s beyond the scope of this review, but Ellenberg shows how this has serious consequences in three-way political races, arguing that Nader tilted the election to Bush over Gore, specifically in Florida. We need to be skeptical about public opinion and all types of polls.

***

One last fun idea from the book: “Bet the guests at a party that two people in the room have the same birthday. It had better be a good-sized party—say there are thirty people there. Thirty birthdays out of 365 options isn’t very many, so you might think it pretty unlikely that two of those birthdays would land on the same day. But the relevant quantity isn’t the number of people: it’s the number of pairs of people. It’s not hard to check that there are 435 pairs of people, and each pair has a 1 in 365 chance of sharing a birthday” (p. 257).

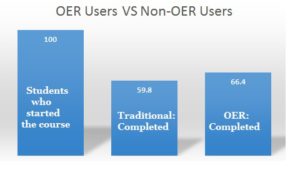

Research to date has shown that, generally speaking, implementing OER has a small positive impact on student success, as measured by getting a C or better in the course, withdrawal and drop rates. This is an important finding because students who have the option of adopting OER save tremendous amounts of money. OER go a long way towards fixing a broken textbook market and should continue to receive more attention based on this fact alone.

I’m not too surprised that switching a curriculum from “closed” to “open” doesn’t have a huge influence. In fact, I am not aware of research that shows a strong “textbook effect,” that is a study that shows how one specific textbook produces dramatically better results than another. In contrast, the massive study, “On Evaluating Curricular Effectiveness” examines 698 peer-reviewed studies of the 13 mathematics curriculum that are supported by the National Science Foundation [~100 million in funding] as well as six different commercial products. They found that “The corpus of evaluation studies as a whole across the 19 programs studied does not permit one to determine the effectiveness of individual programs with a high degree of certainty, due to the restricted number of studies for any particular curriculum, limitations in the array of methods used, and the uneven quality of the studies.” (p.3). If such heavily funded curriculum across nearly 700 studies have only inconclusive results, we should not be surprised that the effects of OER adoption are relatively modest. This leads me to believe that textbooks may not be huge drivers of pedagogical change

At the same time, I do want to emphasize that even if OER adoption leads to only small learning gains, it is still a very valuable enterprise. It saves students significant amounts of money and small learning gains are better than no learning gains. It potentially increases the efficiency of educational enterprise by facilitating the sharing of resources amongst widely distributed faculty who are willing to share and utilize one another’s resources. It can lead to legal collaboration in extraordinary ways – but my present question is, does the “Open” in OER really lead to better student learning outcomes?

In a recent post, I wrote about Hattie’s book, Visible Learning, and shared some of the key interventions he suggests for significantly improving student learning. The question that I want to address is, “How does the ‘Open’ in OER help a teacher implement these interventions?” In other words, assume that all educational resources are free. Is there something special about the legal permissions associated with OER that would make them inherently better in terms of using them to implement Hattie’s interventions that have the largest effect sizes?

The interventions that I identified in the previous post were “set high goals,” “have high expectations,” “giving and receiving feedback,” “spaced feedback,” “direct instruction,” and “strengthening student relationships.”

As I have spent time reviewing and reflecting on these interventions, I have come to tentative conclusion, that actually there is not a huge “open” advantage. The “open” in OER does not appear to make it easier to help students and teachers “set high goals,” or “have high expectations.” “Giving and receiving feedback” and “creating opportunities for spaced feedback” could be done equally well with traditional or open content. OER most likely would not impact “direct instruction” although I do believe that giving students a free textbook could “strengthen student relationships.”

David Wiley has argued that there are open advantages in one of Hattie’s highest-rated interventions: “organizing and transforming.” While it is certainly more legal to publish reorganized versions of open content than traditional content, one could also argue that a transformation of commercial content could be done and turned into the teacher without open content. Whether such an assignment would be more meaningful with open or closed content is naturally debatable.*

So what do I make of all this? While my thoughts are tentative and subject to change, I think the following points should be carefully considered:

- We should grapple with the possibility that the “Open” in OER does not make OER a better pedagogical choice. In other words, it’s possible that simply adopting OER will not lead to significant improvement in educational outcomes (“significant” meaning the types of high effect sizes Hattie says we should be focusing on). Because people learn by doing, we must ask ourselves, “Are there things we can ask students to do with open materials that we can’t ask them to do with traditional materials” and “If yes, do any of those things matter in terms of learning?” The answer to the first question is clearly yes, but based on my analysis of Hattie’s high-impact interventions, my tentative answer to the second question is “not that we have yet discovered.” More attention needs to focus on whether or not there are effective pedagogies that are enabled specifically by openness.

- It is also possible that OER adoption makes a difference in ways not measured by grades or exam scores. Perhaps students who use OER become more likely to be creators in the future, or improve on some other metric we are not currently examining. Thus there might be some be OER impact that traditional effect sizes on standardized tests don’t measure.

- OER adoption should be linked where possible to pedagogical overhauls that do increase learning. For example, if adopting OER leads you to implement a system that includes more frequent student feedback and spaced reviews, then the OER adoption might indirectly lead to better outcomes. This could be a major way that OER improves learning.

- Further attention needs to be paid to what happens when OER are adopted at scale. It is one thing to implement OER into a single course, another to implement it into a whole degree program. The latter might produce results that are different from the former.

- I believe that in terms of increasing learning, the greatest potential for OER itself is increasing access to high-quality information where access is extremely limited (for example, in international ESL contexts). This dramatically increased access will provide learners with the opportunity to act.

- In contexts (such as US higher education) where content is available but overpriced, the largest learning gains will come when OER adoption is paired with pedagogically sound principles, or if we can uncover ways in which the “Open” in OER can be leveraged to help students act in ways that traditional materials don’t easily facilitate.

I would love to hear your thoughts and continue the conversation.

* David Wiley argued passionately regarding disposable assignments VS meaningful assignments. There is no doubt that it is more motivating to write content that will potentially be read by the masses as opposed to just one instructor (or TA!). At the same time, I have a nagging suspicion that if everyone started doing open assignments the influence would diminish because people wouldn’t have enough time to read all the remixed versions. I’m not referring to professors or TAs, I mean that part of the excitement about publishing in the open is that a big blogger will pick up your work and share it broadly. Or perhaps your textbook revisions will be read by later generations of students – this is the type of idea that excites people about renewable assignments. And yet if everybody did this there wouldn’t be enough attention by the community at large to give the students’ products sufficient attention; it would be akin to having students post their assignments on a blog that nobody reads. In other words, I think this is a tremendous idea for individual teachers to apply, but I don’t believe it is a scalable solution.

I recently shared some thoughts from Visible Learning and wanted to also pass on some of my favorite quotes from Visible Learning for Teachers. Not a lot of commentary here, just some highlights from the book.

On the need for diagnostic feedback that tells us what the students know and believe

“David Ausubel claimed: ‘…if I had to reduce all of educational psychology to just one principle, I would say this: ‘The most important single factor influencing learning is what the learner already knows. Ascertain this and teach him accordingly’” (p. 41).

“Shayer (2003) suggests two basic principles for teachers. First, teachers need to think of their role as one of creating interventions that will increase the proportion of children attaining a higher thinking level, such that the students can use and practise these thinking skills during the course of a typical lesson – that is, teachers must attend first to how the students are thinking. If you cannot assess the range of mental levels of the children in your class, and simultaneously what is the level of cognitive demand of each of the lesson activity, how can you plan and then execute – in response to the minute by minute responses of the pupils – tactics which result in all engaging fruitfully?” (p. 43)

“Among the most powerful of all interventions is feedback or formative evaluation – providing information to the teacher as to where he or she is going, how he or she is going there, and where he or she needs to go next. The key factor is for teachers to have mind frames in which they seek such feedback about their influences on students and thus change, enhance, or continue their teaching methods. Such a mind frame – that is, seeking evidence relating to the three feedback questions (‘Where am I going?’; ‘How am I going there?’; ‘Where to next?’) – is among the most powerful influences on student achievement that we know” (p. 182).

What faculty need to agree on across specific courses

- “‘What is it that we want our students to know and be able to do as a result of this unit?’ (Essential learning)

- ‘How will they demonstrate that they have acquired the essential knowledge and skills? Have we agreed on the criteria that we will use in judging the quality of student work, and can we apply the criteria consistently?’ (Success indicators)

- ‘How will we intervene for students who struggle and enrich the learning for students who are proficient?’

- ‘How can we use the evidence of student learning to improve our individual and collective professional practice?’” (p. 70)

On the importance of caring

“When we are asked to name the teachers that had marked positive effects on us, the modal number is usually two to three, and the reasons typically start with comments about caring, or that they ‘believed in me’. The major reason is that these teachers cared that you knew their subject and shared their passion – and aimed always to ‘turn you on’ to their passion. Students know when teachers care and are committed enough, and have sufficient skills, to turn them on to enjoying the challenges and excitement of their subject (whether it be sport, music, history, maths, or technology).

“A positive, caring, respectful climate in the classroom is a prior condition to learning. Without students’ sense that there is a reasonable degree of ‘control’, sense of safety to learn, and sense of respect and fairness that learning is going to take place, there is little chance that much positive is going to occur. This does not mean having rows of adoring students, sitting quietly, listening attentively, and then working cooperatively together to resolve the dilemmas and join in interesting activities; it does mean that students feel safe to show what they do not know, and have confidence that the interactions among other students and with the teacher will be fair and in many ways predictable (especially when they ask for help)” (p. 78)

My cousin recently recommended that I read The Black Swan, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. I thought that it was a very interesting book, although I felt that it could have been shorter Taleb wrote a more concise essay that covers much of the same ground). Here are some of my key takeaways from the book:

A “Black Swan” is an event that is very rare, has extreme impact and with hindsight (but not foresight) was predictable (p. xviii). Taleb writes:

Just imagine how little your understanding of the world on the eve of the events of 1914 would have helped you guess what was to happen next. (Don’t cheat by using the explanations drilled into your cranium by your dull high school teacher). How about the rise of Hitler and the subsequent war? How about the precipitous demise of the Soviet bloc? How about the rise of Islamic fundamentalism? How about the spread of the Internet? How about the market crash of 1987 (and the more unexpected recovery)? Fads, epidemics, fashion, ideas, the emergence of art genres and schools. All follow these Black Swan dynamics. Literally, just about everything of significance around you might qualify.

The central idea of this book concerns our blindness with respect to randomness, particularly the large deviations: Why do we, scientists or nonscientists, hotshots or regular Joes, tend to see the pennies instead of the dollars? Why do we keep focusing on the minutiae, not the possible significant large events, in spite of the obvious evidence of their huge influence? And, if you follow my argument, why does reading the newspaper actually decrease your knowledge of the world?

It is easy to see that life is the cumulative effect of a handful of significant shocks. It is not so hard to identify the role of Black Swans, from your armchair (or bar stool). Go through the following exercise. Look into your own existence. Count the significant events, the technological changes, and the inventions that have taken place in our environment since you were born and compare them to what was expected before their advent. How many of them came on a schedule? Look into your own personal life, to your choice of profession, say, or meeting your mate, your exile from your country of origin, the betrayals you faced, your sudden enrichment or impoverishment. How often did these things occur according to plan? (p. xviii-xix).

In other words, the things that we expect and plan for tend not to have a large impact, because the impact has already been mitigated against. In contrast, unexpected events have a huge impact. I was not planning to meet my wife on December 4, 1998, and there are many other personal examples where an unplanned for event led to significant results.

A key suggestion then in the business world is that in order to make a quantum leap forward in some aspect of business, we need to have some type of unexpected, unanticipated idea that people are not currently thinking about (because if they were currently thinking about it, it would have already happened).

A recurring idea in the book is that we have a strong tendency to tell a narrative story to explain the unexplainable. Creating these narratives simplifies our world, which “pushes us to think that the world is less random than it actually is” (p. 69). One of the many ways that Taleb discusses this is by explaining the “the triplet of opacity. They are:

- the illusion of understanding, or how everyone thinks he knows what is going on in a world that is more complicated (or random) than they realize;

- the retrospective distortion, or how we can assess matters only after the fact, as if they were in a rearview mirror (history seems clearer and more organized in history books than in empirical real ity); and

- the overvaluation of factual information and the handicap of authoritative and learned people” (p.8).

Taleb frequently rails against the “ludic fallacy” which is “basing studies of chance on the narrow world of games and dice” (p.309). The bell curve is a frequent application of the ludic fallacy to randomness.

In other words, we do not see the randomness in the world, instead creating causality where it does not exist. We also tend to unjustifiably place a premium value on the words of experts who actually do not know any more than the average taxi driver.

One of my favorite examples of the book concerns the turkey and 1,001 days of history. A turkey is fed every day for a 1,000 days—each day confirms statistically that the human race cares about its happiness. But on day 1,001 the turkey gets an unpleasant surprise. “Consider that the feeling of safety reached its maximum when the risk was at the highest!” (p. 41).

Taleb points to real examples where this has happened such as the safety of mortgages (before the crash in 2008) or this quote from E.J. Smith, captain of the Titanic: “When anyone asks me how I can best describe my experience in nearly forty years at sea, I merely say, uneventful. Of course there have been winter gales, and storms and fog and the like. But in all my experience, I have never been in any accident… or any sort worth speaking about. I have seen but one vessel in distress in all my years at sea. I never saw a wreck and never have been wrecked nor was I ever in any predicament that threatened to end in disaster of any sort.” That quote was uttered in 1907, the Titanic crashed in 1912.

All of this is rather grim news. Our future is likely to be highly impacted by events that we cannot foresee or protect against. So what can we do? Potential remedies include recognizing that you’re actually not certain about an occurrence and be open to additional possibilities. How can you do this?

One way is to look for falsifying instances, occasions in which a certain theory did not hold true. He cites an experiment done by P.C. Wason.

Wason presented subjects with the three-number sequence of 2, 4, 6 and asked them to try to guess the rule generating it. Their method of guessing was to produce other three-number sequences, to which the experimenter would response “yes” or “no” depending on whether the new sequences were consistent with the rule. Once confident with their answers, the subjects would formulate the rule.

The correct rule was “numbers in ascending order,” nothing more. Very few subjects discovered it because in order to do so they had to offer a series in descending order (that they experimenter would say “no” to). Wason noticed that the subjects had a rule in mind, but gave him examples aimed at confirming it instead of trying to supply series that were inconsistent with their hypothesis. Subjects tenaciously kept trying to confirm the rules that they had made up (p. 58).

In other words people look for confirming evidence that their plans are correct, when looking for disconfirming evidence that their plans might not be right would be more effective.

Another strategy for clearer thinking is to consider the silent evidence. That is observe carefully what is not being said and who is not saying it. Taleb writes:

Numerous studies of millionaires aimed at figuring out the skills required for hotshotness follow the following methodology. They take a population of hotshots, those with big titles and big jobs, and study their attributes. They look at what those big guns have in common: courage, risk taking, optimism, and so on, and infer that these traits, most notably risk taking, help you to become successful. You would also probably get the same impression if you read CEOs’ ghostwritten autobiographies or attended their presentations to fawning MBA students.

Now take a look at the cemetery. It is quite difficult to do so because people who fail do not seem to write memoirs, and, if they did, those business publishers I know would not even consider giving them the courtesy of a returned phone call (as to returned e-mail, fuhgedit). Readers would not pay $26.95 for a story of failure, even if you convinced them that it had more useful tricks than a story of success. The entire notion of biography is grounded in the arbitrary ascription of a causal relation between specified traits and subsequent events. Now consider the cemetery. The graveyard of failed persons will be full of people who shared the following traits: courage, risk taking, optimism, et cetera. Just like the population of millionaires. There may be some differences in skills, but what truly separates the two is for the most part a single factor: luck (p. 106-107).

In other words, these attributes seem to be the key to success, but many people who did not obtain wild success also had these same attributes. As you have already guessed Taleb believes the success came from luck, not from attributes.

Taleb applies these basic principles to government as well:

Katrina, the devastating hurricane that hit New Orleans in 2005, got plenty of politicizing politicians on television. These legislators, moved by the images of devastation and the pictures of angry victims made homeless, made promises of “rebuilding.” It was so noble on their part to do something humanitarian, to rise above our abject selfishness.

Did they promise to do so with their own money? No. It was with public money. Consider that such funds will be taken away from somewhere else, as in the saying “You take from Peter to give to Paul.” That somewhere else will be less mediatized. It may be privately funded cancer research, or the next efforts to curb diabetes. Few seem to pay attention to the victims of cancer lying lonely in a state of untelevised depression. Not only do these cancer patients not vote (they will be dead by the next ballot), but they do not manifest themselves to our emotional system. More of them die every day than were killed by Hurricane Katrina; they are the ones who need us the most – not just our financial help, but our attention and kindness. And they may be the ones from whom the money will be taken – indirectly, perhaps even directly. Money (public or private) taken away from research might be responsible for killing them – in a crime that may remain silent.

…We can see what governments do, and therefore sing their praises-but we do not see the alternative. But there is an alternative; it is less obvious and remains unseen (110-111).

Taleb suggests that we need to keep our minds open to a variety of possibilities. He writes:

Show two groups of people a blurry image of a fire hydrant, blurry enough for them not to recognize what it is. For one group, increase the resolution slowly, in ten steps. For the second, do it faster, in five steps. Stop at a point where both groups have been presented an identical image and ask each of them to identify what they see. The members of the group that saw fewer intermediate steps are likely to recognize the hydrant much faster. Moral? The more information you give someone, the more hypotheses they will formulate along the way, and the worse off they will be. They see more random noise and mistake it for information.

The problem is that our ideas are sticky: once we produce a theory, we are not likely to change our minds—so those who delay developing their theories are better off. When you develop your opinions on the basis of weak evidence, you will have difficulty interpreting subsequent information that contradicts these opinions, even if this new information is obviously more accurate.

Taleb brings up the work of Tetlock to point out again that experts often are no better predictors than the average well-informed person.

To mitigate against the invariably incorrect predictions that people will encounter he suggests being cautious of the variability factor, meaning, don’t take any projections too seriously. Further explore the range of possibilities in the forecast and the probabilities of each.

In some ways this book is depressing. If so much of the world is randomness, are all my plans pointless? Well, mostly yes, it seems Taleb would say, but he does give a few ideas in his chapter called “What do you do if you cannot predict?”

Accept that being human involves some amount of epistemic arrogance in running your affairs. Do not be ashamed of that. Do not try to always withhold judgment—opinions are the stuff of life. Do not try to avoid predicting—yes, after this diatribe about prediction I am not urging you to stop being a fool. Just be a fool in the right places.

What you should avoid is unnecessary dependence on large-scale harmful predictions—those and only those. Avoid the big subjects that may hurt your future: be fooled in small matters, not in the large. Do not listen to economic forecasters or to predictors in social science (they are mere entertainers), but do make your own forecast for the picnic. By all means, demand certainty for the next picnic; but avoid government social-security forecasts for the year 2040.

The reader might feel queasy reading about these general failures to see the future and wonder what to do. But if you shed the idea of full predictability, there are plenty of things to do provided you remain conscious of their limits. Knowing that you cannot predict does not mean that you cannot benefit from unpredictability.

The bottom line: be prepared! Narrow-minded prediction has an analgesic or therapeutic effect. Be aware of the numbing effect of magic numbers. Be prepared for all relevant eventualities (p.203).

Seize any opportunity, or anything that looks like opportunity. They are rare, much rarer than you think. Remember that positive Black Swans have a necessary first step: you need to be exposed to them. Many people do not realize that they are getting a lucky break in life when they get it. If a big publisher (or a big art dealer or a movie executive or a hotshot banker or a big thinker) suggests an appointment, cancel anything you have planned: you may never see such a window open up again. I am sometimes shocked at how little people realize that these opportunities do not grow on trees. Collect as many free nonlottery tickets (those with open-ended payoffs) as you can, and, once they start paying off, do not discard them. Work hard, not in grunt work, but in chasing such opportunities and maximizing exposure to them. This makes living in big cities invaluable because you increase the odds of serendipitous encounters—you gain exposure to the envelope of serendipity. The idea of settling in a rural area on grounds that one has good communications “in the age of the Internet” tunnels out of such sources of positive uncertainty. Diplomats understand that very well: casual chance discussions at cocktail parties usually lead to big breakthroughs—not dry correspondence or telephone conversations. Go to parties! If you’re a scientist, you will chance upon a remark that might spark new research (p.208-209).

Another interesting application of large events that we cannot predict concern volatility in the stock market. Taleb points out that “by removing the ten biggest one-day moves from the U.S. stock market over the past fifty years, we see a huge difference in returns” (the S&P going from essentially 0 to 1000 instead of 2500), (p. 276).

There are many other summaries of The Black Swan, one of my favorites is here.

***

Somewhat related to The Black Swan is another book I recently read, Nonsense, by Jamie Holmes. The basic premise of this book is that we live in a world with lots of ambiguity – and humans by nature don’t like ambiguity. So we need to learn how to effectively manage our dislike ambiguity because it isn’t going away. In other words, as in The Black Swan, we want to create causality or come to quick narrative conclusions about why the world is the way it is.

He reports on several interesting scientific studies. For example, in examining the question, “Could even small amounts of extra stress affect our willingness to dwell in uncertainty?” he cites a study where participants who were making decisions in the presence of annoying sounds were more likely to make decisions faster and with less rationality than their peers without the annoying sound. In another study, those who were asked to evaluate a candidate for a prospective job. Some subjects heard positive things about the candidate and then negative, while others heard the negative information first and then the positive. When subjects had time to “think about their appraisals, they rated candidates at about a five, regardless of whether the flattering facts emerged earlier or later. But when subjects had to make a decision quickly, job applicants with strong first impressions were rated at a 7 on average, while candidates with faults conveyed early on were rated at a 3…in both cases, it wasn’t merely that subjects formed their impressions faster, but they also ignored the later, contradictory information” (p. 75). Other studies showed that under time pressure, “group members who voiced opposition to a given consensus were more quickly marginalized and ignored. Another study found that when a stressful noise was present, group members were again less tolerant of any information that conflicted with their beliefs” (p. 78).

Holmes points out that humans tend to want closure – they want to quickly come to conclusions and move forward – but this is difficult in ambiguous situations. He shares an instrument that people can take to determine the extent to which they need quick closure (those who know me well will accurately guess that was above average in terms of having a greater need for closure). People like me need to know that their minds’ “natural aggressiveness in papering over anomalies, resolving discrepancies, and achieving the ‘miracle of simplification’ is set a bit higher” (p. 88).

The rush to closure manifests itself in a variety of settings. In medicine, Homes points out that “the most common diagnostic error in medicine is premature closure –when a physician stops seeking a diagnosis after finding one that explains most of or even all the key findings, without asking…what else could this be” (p. 120). He shares a series of scary experiments and anecdotes that show that in medicine misdiagnoses can occur all too easily.

So what do we do? I wish that more of the book had been addressed to this issue. While there are a few nuggets (e.g., Holmes states, “Managing our dangerous but natural urge to demolish ambiguous evidence or deny ambivalent intentions isn’t easy. But it is possible. A good first step is to acknowledge that ambivalence is a far more common state of mind than most people assume” (p. 108)). I believe some of Taleb’s ideas (e.g., look for falsifying evidence, consider the silent evidence, etc.) can help us in this endeavor.

One example of this in the book was a study where “researchers asked participants to pretend that they were members of a race-car team. Facing the risk of engine failure due to a gasket malfunction, the subjects had to decide whether to go ahead with an upcoming race. They were told that the gasket had failed during a certain number of races, but (as the experiment as conducted online) they had to click on a link for ‘additional information, if needed,’ to learn how many timesi the gaskethadn’t failed. Clicking the link would let them in on a truly dire statistic: there was a 99.99 percent chance of gasket failure…Seventy nine percent of the subjects made the mistake of electing to go ahead and race, generally because participants failed to seek out the additional information” (p. 171).

Holmes also recommends getting creative. For example, consider a riddle this this one: “. A windowless room contains three identical light fixtures, each containing an identical light bulb or light globe. Each light is connected to one of three switches outside of the room. Each bulb is switched off at present. You are outside the room, and the door is closed. You have one, and only one, opportunity to flip any of the external switches. After this, you can go into the room and look at the lights, but you may not touch the switches again. How can you tell which switch goes to which light?” (p. 190). If one only thinks of visually seeing the lights go off and on, it is an intractable problem. But if I think about the fact that lightbulbs, when turned on, give off heat, that may give me the help that I need. Looking at a different angle makes all the difference.

So in summary, what did I gain from these two books?

- I have a tendency to want to create a narrative for why things are the way that they are. This narrative may or may not be right, but I will tend to ascribe more certainty that it is right than is probably justified.

- I can work to overcome this tendency by reminding myself of its existence. I can also look at situations in new ways, asking for disconfirming or silent evidence. I can also seek out additional information, particularly from those who might have a different point of view than I have.

- I should generally not put stock in long-range predictions because there are many looming Black Swans that will radically reshape how the world works.

- I should spend less time trying to make something happen and be more open to serendipitous opportunities and capitalize on those when then take place.

One of my favorite books about teaching is Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Acheivement, by John Hattie. In this book he synthesizes over 800 meta-analyses of education interventions with the idea of looking for key, proven pedagogical strategies that educators (and parents) can implement. One of his more important arguments is that almost all interventions have some effect size; therefore, our focus should be on high-effect-size interventions (or easy-to-implement interventions). A summary of all the interventions he studied ishere, and a summary of his excellent subsequent book Visible Learning for Teachers is here.

My primary interest in returning to Hattie’s book for the third time (yes, I have read it three times!) was to think about how OER could leveraged to better help accomplish some of the interventions Hattie found to be most effective. In other words, assuming that all learning materials were free of charge, would the “open” in OER make a difference in implementing any of these high-impact interventions?

In this post I’m going to list the interventions that I considered to be the best contenders for interventions that could be readily applied in a college environment (several of the interventions focus on issues relating to elementary school). Because I have six kids, I also read with the lens of a parent and will throw in some of those ideas at the end. In a future post, I’ll explore how OER could make a difference in some of these areas, at the present I’m just focused on listing and explaining some of the key interventions. I would welcome your thoughts on how OER could make a difference in these areas.

Ideas for Teachers to Consider

Help Students Set High Goals

“A major finding…is that achievement is enhanced to the degree that students and teachers set challenging goals…There is a direct linear relationship between the degree of goal difficulty and performance…and the overall effect size is a large (d =.67)…The performances of students who have the most challenging goals are over 250% higher than the performances of subjects with the easiest goals” (p. 164).

“Difficult goals are much better than ‘do your best’ or no assigned goals…Instead, teachers and learners should be setting challenging goals. Goals can have a self-energizing effect if they are appropriately challenging for the students as they can motivate students to exert effort in line with the difficulty or demands of the goal” (p.164).

Create a course with challenging expectations. Where possible, give students the opportunity to set goals that will help them stretch. Give them a vision of what can be accomplished and motivate them to do so.

Strengthen Student Relationships

Teacher-student relationships has a large effect size (d =.72). “Building relations with students implies agency, efficacy, respect by the teacher for what the child brings from class…and allowing the experiences of the child to be recognized in the classroom. Further, developing relationships requires skill by the teacher – such as the skills of listening, empathy, caring, and having positive regard for others” (p. 118).

Have High Expectations

“In the education system, it is now widely accepted that teachers do form expectations about student ability and skills and that expectations affect student achievement (Dusek and Joseph, 1985). The question is not ‘Do teachers have expectations?’ but ‘Do they have false and misleading expectations that lead to decrements in learning or learning gains-and for which students?” (p. 121)…Teachers must stop over-emphasizing ability and start emphasizing progress…stop seeking evidence to confirm prior expectations but seek evidence to surprise themselves, find ways to raise the achievement of all…and be evidence-informed about the talents and growth of all students by…being accountable for all” (p. 124).

“Having low expectations of the students’ success is a self-fulfilling prophecy…how to invoke high standards seems critical and this may require more in-school discussion of appropriate benchmarks…” (p. 127). Overall effect size (d =.43).

Give and Receive Feedback

“When teachers seek, or at least are open to, feedback from students as to what students know, what they understand, where they make errors, when they have misconceptions, when they are not engaged – then teaching and learning can be synchronized and powerful” (p. 173). “About 70 percent of teachers claim they provided…detailed feedback often or always, but only 45 percent of students agreed with their teachers’ claims. Further, Nuthall (2005) found that most feedback that students obtained in any day in classrooms was from other students and most of the feedback was incorrect” (p. 174)…. “The emphasis should be on what students can do, and then on students knowing what they are aiming to do, having multiple strategies for learning to do, and knowing when they have done it” (p. 199). (d =.73).

Create Opportunities for Spaced Practice

“It is the frequency of different opportunities rather than merely spending ‘more’ time on task that makes the difference to learning” (p. 185). “Nuthall (2005) claimed that students often needed three to four exposures to the learning – usually over several days – before there was a reasonable probability they would learn. This is consistent with the power of spaced rather than massed practice….Students in spaced practice conditions performed higher than those in massed practice conditions (d=.46). Others found higher effect sizes, with an overall effect size (d =.71).

Direct Instruction

“Direct Instruction has a bad name for the wrong reasons, especially when it is confused with didactic teaching, as the underlying principles of Direct Instruction place it among the most successful outcomes (d = .59). Direct Instruction involves seven major steps:

- Before the lesson is prepared, the teacher should have a clear idea of what the learning intentions What, specifically, should the student be able to do, understand, care about as a result of the teaching?

- The teacher needs to know what success criteria of performance are to be expected and when and what students will be held accountable for from the lesson/activity. The students need to be informed about the standards of performance.

- There is a need to build commitment and engagement in the learning task. In the terminology of Direct Instruction, this is sometimes called a “hook” to grab the student’s attention. The aim is to put students into a receptive frame of mind; to focus student attention on the lesson; to share the learning intentions.

- There are guides to how the teacher should present the lesson–including notions such as input, modeling, and checking for understanding. Input refers to providing information needed for students to gain the knowledge or skill though lecture, film, tape, video, pictures, and so on. Modeling is where the teacher shows students examples of what is expected as an end product of their work. The critical aspects are explained through labeling, categorizing, and comparing to exemplars of what is desired. Checking for understanding involves monitoring whether students have “got it” before proceeding. It is essential that students practice doing it right, so the teacher must know that students understand before they start to practice. If there is any doubt that the class has not understood, the concept or skill should be re-taught before practice begins.

- There is the notion of guided practice. This involves an opportunity for each student to demonstrate his or her grasp of new learning by working though an activity or exercise under the teacher’s direct supervision. The teacher moves around the room to determine the level of mastery and to provide feedback and individual remediation as needed.

- There is the closure part of the lesson. Closure involves those actions or statements by a teacher that are designed to bring a lesson presentation to an appropriate conclusion: the part wherein students are helped to bring things together in their own minds, to make sense out of what has just been taught. “Any questions? No. OK, let’s move on” is not closure. Closure is used to cue students to the fact that they have arrived at an important point in the lesson or the end of a lesson, to help organize student learning, to help form a coherent picture, to consolidate, eliminate confusion and frustration, and so on, and to reinforce the major points to be learned. Thus closure involves reviewing and clarifying the key points of a lesson, trying them together into a coherent whole, and ensuring they will be applied by the student by ensuring they have become part of the student’s conceptual network.

- There is independent practice. Once students have mastered the content or skill, it is time to provide for reinforcement practice. It is provided on a repeating schedule so that the learning is not forgotten. It may be homework or group or individual work in class. It is important to note that this practice can provide for decontextualization: enough different contexts so that the skill or concept may be applied to any relevant situation and not only the context in which it was originally learned. For example, if the lesson is about inference from reading a passage about dinosaurs, the practice should be about inference from reading about another topic such as whales. The advocates of Direct Instruction argue that the failure to do this seventh step is responsible for most student failure to be able to apply something learned.

In a nutshell: The teacher decides the learning intentions and success criteria, makes them transparent to the students, demonstrates them by modeling, evaluates if they understand what they have been told by checking for understanding, and re-telling them what they have told by tying it all together with closure (see Cooper, 2006)” (p. 205-206).